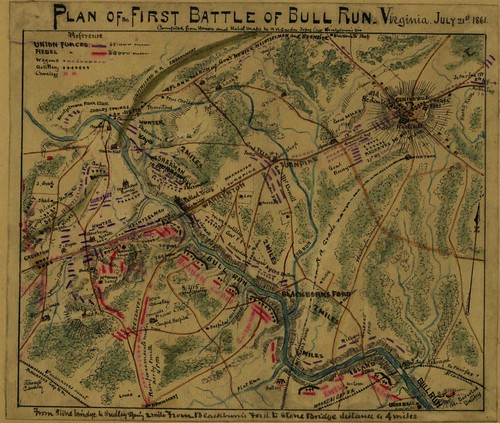

However, for those unfamiliar with battlefield maps, they can be very intimidating and unclear. Without a foundation of knowledge about the battle, this problem is exacerbated. For example, take a look at this map of the First Battle of Bull Run.

Plan of the First Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. July 21st 1861. Compiled from Union and Rebel Maps by R.K. Sneden, Topog. Engr. Heintzelman's Div. Accessed from the Library of Congress Maps Collection at this link.

What are we really looking at here? (if this is too small, access the original record at this link, or view the map here. There are some geographical features of the area - some water, some roads, some trees, kind of a funny looking thing up near the right hand top corner. There are some red lines and some blue lines, and a whole bunch of names. But what does all of this MEAN, and how does it help the viewer to understand the battle?

Not all maps are the same, of course, and while this one has a key, many do not, but there are a few things that are generally true. First, red is almost always Confederate Forces, and Blue is almost always Union Forces. Names given are generally of the brigade commander, but this is less universal and harder to rely on. Important places in general (such as the town of Centerville near the top right corner, or the Warrenton Turnpike, which runs diagonally across the map) are always shown, and places that are important in the battle (such as Blackburns Ford, in the lower center of the map) are also usually labeled. As with in any map, before even worrying about the details, it's worth examining it a few minutes and figuring out what it DOES tell you, such as - on this example - how the railroads are narked, what direction is north, and that the parallel lines along Bull Run denote the steepness of the banks, and that other hills such as the hill where Henry House is (on the left hand side just below center) is located.

For a battle map, the next step is to figure out where the conflict is actually taking place. While this might seem obvious, this is generally where the largest numbers of troops from the two sides are standing - but remember, these groups do not stand still. The only way to really understand a battle is to combine an examination of maps with a narrative account of the battle. Otherwise, for example, you can't tell that Sherman (in this map, the cluster of troops marked Sherman can be found just north of the Warrenton Pike, and on the east side of Bull Run) is soon to charge across a nearby ford and attack the Confederate forces on the other side of the river. A concise, simple description of the battle is of inestimable aid when staring at a map like this - but such a description is not for this blog post. Instead, I'm going to outline a strategy for helping a map like this come alive.

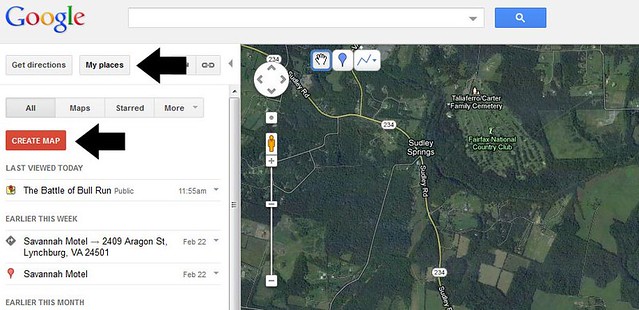

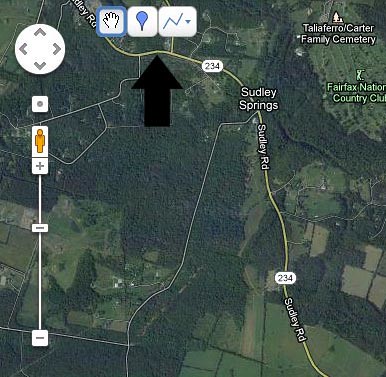

No amount of looking at this map will you tell you who these people were or what the land on which they stood really looked like. However, with the internet, you can get a long way towards doing understanding this better. This is where Google Maps comes in. By combining what a simple battlefield map such as this one can tell us with the plethora of images that can be found on the internet, those trying to learn about a battle can really get in-depth with it, by recreating this map using a custom Google Map. To do this, you will need to have a Google Account and be logged in. Then, go to www.google.com/maps. Select "My Places", then select "Create Map."

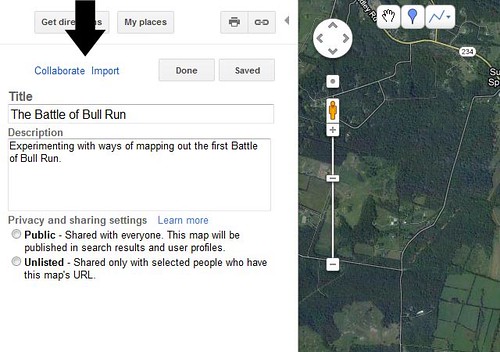

Once you have created your map, you fill in the name you'd like to use, and a description. If you are working with a group - for example, a class of students - you can also select "Collaborate," which will give you the option to share the map with any number of other people who can also add features to it.

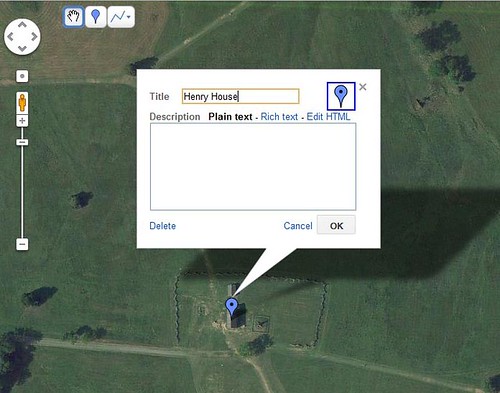

Once you've got the basic set up, it's time to start adding things to your map! You can add either pins or lines, by using these two buttons:

The one on the left that looks like an inverted tear drop lets you drop a pin; the one on the right lets you draw a line! Dropping a pin looks like this:

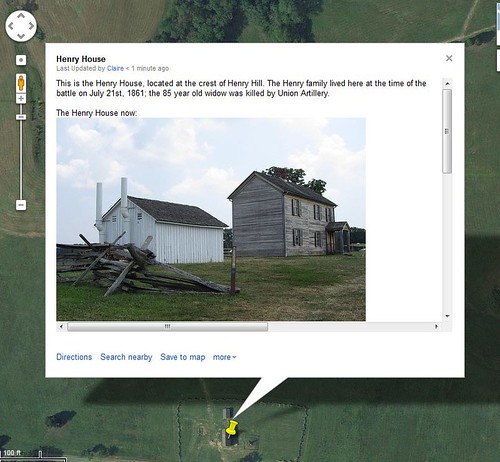

You write in the name you want, and a description of the place. You can even copy and paste pictures in to the description! If you click on the representation of the pin in the upper right hand corner, you can change how the pin looks, too. In short, there are a LOT of options. Once you've created a pin, and added what you want, you can save it, and click "Done" over on the left (above the name of your map) and when you got to look, you'll see your pin - and when you click it, the description you wrote will pop up:

I popped in a picture of the Henry House that I took when I visited Bull Run last summer; scrolling down, there is a historical picture of how the house looked after the battle (you can see that image here.) Now you know the basics! Play around until your comfortable with it - Google gives a bunch more information on how to make custom maps here.

So, you've got a map. How can you use it to help teach about the Battle of Bull Run? Lots of ways!

- Have students figure out where important events took place, and place pins there.

- Track down images of important figures and sites around the battle field, and use them to illustrate the map (make sure you check copyright information on all such images before using them, though!

- Add historical data to the description.

- Use different colored pins to mark different kinds of locations.

- Collaboratively trace - using lines - the different ways that units came and went from the battlefield.

For getting images, I highly recommend using the Library of Congress American Memory online collection, which hosts a truly amazing number of resources of all kind related to US History, nearly all of which is in the public domain and therefore can be legally used (still cite your sources, though). Just search for what you're looking for!

That's a quick-and-dirty explanation of how Google Maps can be used to help clarify the use of battlefield maps. There's nothing like building your OWN map to help one understand where every one was, why they were there, and what the prominent features of the area were. Going through the process oneself can really help to elucidate maps that seem very cryptic when just glanced at. I've gone ahead and populated my Google Map of Bull Run with many more important features; you can take a look by going to this link. At the time of writing this, it's still a work in progress, but it does demonstrate the various possibilities described in this post!

Next time - more on Bull Run! A strategy for sorting out the confusing back-and-forth and timing issues that come up while trying to navigate this kind of map!